Deadly Premonition is a strange, strange game. Strange both in the fact that the cult hit budget title jam-packed with weird, quirky moments, mildly insane writing, and off-beat voice acting. But also strange in the sense that we’ve given it almost two full playthroughs and we’re still not sure if it’s good or not. The combat gameplay’s atrocious, the open-world is perhaps one of the clumsiest ever implemented, the story is deranged, and the whole thing constantly veers between good, so bad-it’s-good, and bad.

There’s one part of the game that we unreservedly love though, and the reason you should pay the pocket change needed to pick it up: its hero, Francis York Morgan. He’s well-written, well-acted, funny, and likeable, sure. But he’s also, honestly, one of the most important protagonists in gaming– one who’s wholly unique, one who could only exist in this particular medium, and one that should be studied by anyone trying to create games. (WARNING: Spoilers for Deadly Premonition follow.)

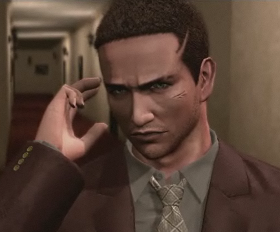

Francis York Morgan– just call him York, everybody else does –is a bit of an oddball. He’s basically all the weird parts of Agent Cooper from Twin Peaks, Agent Mulder from The X-Files, and a hefty dose of schizophrenia. He receives messages in his coffee, is obsessed with 80’s movies, and is cocky to the point of being unbearable. He’s also incredibly kind-hearted, brilliant, a crack shot, and the FBI’s greatest detective. This is what brings him to the sleepy town of Greenvale: he’s investigating the murder of a young girl, believing it to be connected to a string of other cases he’s worked on.

But what really makes York special is his imaginary friend. He speaks constantly to a “Zach”– a secondary personality that helps him solve mysteries, tells him where to go, and gives him extraordinary deductive powers and psychic sensitivity. This Zach, you’ll realize fairly early on, is you, the player. When you nail one of the game’s enemies in the head, York mutters “great shot, Zach!” When you open the start menu, it takes the form of the Red Room– the dimension that Zach resides in, outside of time (thus pausing the game). When working on a crime scene, you find the clues that are highlighted and point them out to York, who makes deductions. Even the game’s quick-time events have a neat justification– they all occur at times when York is panicking and scared, and you hammering buttons and waggling sticks is to keep him focused and brave.

This is a brilliant overlap of game design and narrative. First, and most obviously, it provides a great way to frame York’s actions as a player character. He’s erratic, detached, and unpredictable because he’s never really in control, instead taking orders from a being outside the world. York never questions Zach– if you want to blow off the case to go fishing, drive around in the rain, collect the skeleton of a separate, unrelated murder victim, you can. York trusts you completely, and won’t even eat or shave unless Zach tells him he needs to. At one point, York is captured and you need to go find another character and guide them to him. What in other games is immersion-breaking– the disconnect between the player and their avatar –is here a central part of the story. York could only exist in games because the central element of his internal conflict, his mental illness and his need for a friend to guid and protect him, is expressed entirely as a form of game mechanics.

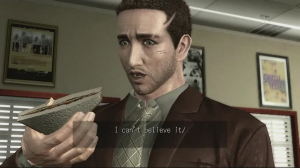

It’s also just wonderful storytelling, as it creates a bond between player and protagonist. We’d routinely throw the game’s other characters out of the car so that we could drive alone with York, talking about the Superman movies and Jaws. Although a lot of the game’s writing is strange and nonsensical, the moments between Zack and York always feel warm and friendly, putting the serial killer mystery on the back burner so that York can talk about movies or ask you for dating advice. Whereas most game heroes are loners, York actively reaches out to the player. And even though there’s murders to solve, lives to save, and coffee to drink, Deadly Premonition is at its core the story of York and Zach’s relationship. If Zach wasn’t the player, the climactic twist– [highlight to reveal] that Zach is York’s childhood self who suffered a grievous trauma, and York has been looking after their shared body for years, talking to Zach and giving Zach control to try and draw him back into the real world –would seem hokey. The twist seems tired when told in third-person, but when you’re involved in the story, when it’s about you and York’s relationship, it’s a surprising and powerful moment. Like Bioshock, it’s a twist that redefines your role in the game, turning the “player” of the game into a real character in it. It’s not exactly Bioshock’s level of writing excellence and wit, but it’s an incredibly interesting and unique twist in the middle of a game that seemed like a cheesy, weird horror-comedy.

Like Bioshock, Deadly Premonition (and there’s a sentence you never thought you’d see game critics start) is about finding an emotional core to what the player accepts as standard mechanics. Whereas Bioshock took player agency as its core–making the player the protagonist, not just their controller — Premonition is about finding the emotion implicit in the difference between the player and their protagonist. York is brave and professional (one of the best lines in the game is when he tells a supernatural monster with godlike power that “you’re a first-degree murderer. And I’m a federal agent. Of course you’re going to lose.”), but he’s also profoundly lonely, more scared by falling in love than by ghosts and demons. He may seem like a super-detective with no social skills to other characters, but the player sees him in his intimate moments, when he’s weak and needs help. When he’s in the most dangerous situations, it’s not just an issue of the player being threatened, but the character that they’ve been protecting and guiding. It changes the way you look at a character, and creates a relationship between them and you that wouldn’t exist in another game.

The game’s ending is an especially beautiful use of this. By the end of the game, York’s trauma is revealed. He’s faced down the monster responsible for his parents’ deaths, he’s stopped the killings he’s spent years chasing, and he’s pulled Zach back into the world. But there’s a problem: Zach no longer needs him. Not only that, but Emily, the woman that York loved, is dead. And so you lie down in your hotel room. You discuss the case, as you have at the end of every mission, and talk about what’s happening next. And the protagonist asks the player if they’re ready to say goodbye.You can keep playing if you select “no,” but because the game is fundamentally about your relationship with York it doesn’t end until that relationship does. The last action you, as a player take– the last button you press –is selecting “yes.” From that point on, the story plays out via cutscene, as you can only watch as the character you’ve spent the game guiding goes on to live his life without you. For all of Deadly Premonition‘s faults– Dreamcast-level graphics, awful combat, out-of-place and poorly-thought-out open world, bizarre survival mechanics, strange writing, unbelievable characters, unbalanced weapons, unintuitive sidequests, fishing minigames, uneven pacing –it’s a fantastic ending, one that mines the mechanics of the game for a wealth of emotion.